In-Depth

The Evolving Thin Client and Endpoint Landscape

I recently wrote an article about my experience repurposing an old Windows 10 laptop using 10ZiG's RepurpOS to evaluate its ability to handle modern VDI/DaaS and SaaS workflows.

I tested the system by connecting it to a Horizon VDI desktop and running Microsoft Office applications, Zoom, and streaming videos. I then, recognizing the importance of SaaS, ran Office 365 and other web apps locally on it (without a remote desktop) and found the performance was just as good as on my Windows 11 laptop. After running these tests, I found RepurpOS to be a stable, capable, and cost-effective solution for organizations looking to improve security and extend the life of their legacy PCs.

This made me think about how the thin client has evolved over the years to get us to where we are today.

The Early Years

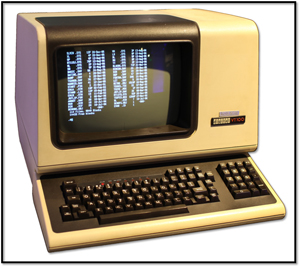

The thin clients that we know today are the direct descendants of the dumb terminals. The purpose of these devices was to connect users to a more powerful computer, starting with mainframes, and later to minicomputers like DEC's widely popular PDP-11. They were text-based and had black, green, or, if you were lucky, amber text. They had only a monitor and a keyboard, as advanced input technologies such as mice had not yet been invented. IBM 3270, ADM-3, Hazeltine, and DEC VT100 were among the more popular brands.

[Click on image for larger view.]

[Click on image for larger view.]

In the late 1980s and 1990s, companies like Wyse expanded the market by moving from simple video terminals to purpose-built thin-client hardware and software. During this time, Sun Microsystems introduced the Sun Ray stateless client as an alternative approach to centralized desktops for its Unix desktop systems. Those early designs laid the groundwork for today's virtual desktop infrastructure (VDI) and cloud-workspace models.

The Desktop Years

Through the 2000s, the market diversified: specialist vendors such as Wyse, Neoware, Sun, etc. competed to provide the best thin-client experience for VDI. One of the most popular thin clients of the time, and the first one I used, was a Wyse VX0 circa 2007; it was a fanless thin client powered by an 800 MHz VIA Eden CPU, had 512 MB of RAM, and 128 MB of flash storage.

[Click on image for larger view.]

[Click on image for larger view.]

As the demand grew and matured, consolidation in the field occurred, with the larger players swallowing some of the early suppliers. For example, Neoware was acquired by Hewlett-Packard in 2007, and Wyse was bought by Dell in 2012, as large server, storage, and PC vendors sought to offer end-to-end desktop solutions.

Modern Thin Clients

Two technology trends kept thin clients relevant. First, desktop remote-display protocols and VDI platforms improved: Citrix's ICA and Microsoft's RDP (and later offerings from VMware and others) made remote desktops practical and responsive across a wider variety of use cases. Second, the early era of cloud computing, DaaS (Desktop-as-a-Service), and improvements in endpoint hardware made modern thin and zero clients far more capable than their terminal ancestors, enabling them to handle multimedia, multiple monitors, USB redirection, and secure boot scenarios while remaining centrally manageable.These companies took advantage of the x86 market's economies of scale and used PC hardware for their thin clients. New form factors emerged, including all-in-one devices with the computer built into the monitor, which were popular in the healthcare industry. A modern example of this is the 10Zig 7911q, which has an Intel N5100 Quad Core running at 1.1 GHz (2.8 GHz Burst), AIO Monitor (1920 x 1080), 16GB DDR4 RAM, and 256GB Storage.

[Click on image for larger view.]

[Click on image for larger view.]

As the market matured, companies shifted away from hardware to management and lifecycle services. Vendors competed on device security, management, and compatibility with cloud and hypervisor stacks rather than on bespoke hardware; in fact, many thin-client companies left the thin-client hardware business altogether and focused on the more profitable operating system side of the house. For example, IGEL quit selling hardware in early 2023 to focus on the more profitable software side of the business. Today's thin-client landscape is a mix of hardware makers, OS vendors, and software/platform companies.

Last Year's Consolidation

Over six months last year, we saw two successful thin-client companies get acquired, the thin-client operating system market further consolidate, and effectively collapse into a few players.

[Click on image for larger view.]

[Click on image for larger view.]

The first major announcement was on Jan. 22, 2025, when VDI behemoth Citrix announced its acquisition of Unicon, the German developer of the eLux thin-client operating system.

This was a shock to the community, as Citrix has always relied on a vast ecosystem of third-party thin-client vendors to deliver its apps and desktops. However, with the "End of Life" for Windows 10 looming, Citrix saw this as an opportunity to control the entire user experience, and its accompanying budget, from the remote desktop down to the physical device. By buying Unicon, Citrix didn't just buy an OS; it bought the ability to offer a turnkey, end-to-end solution and charge its customers accordingly.

The acquisition of eLux allowed Citrix to offer a "Citrix Ready" endpoint OS natively. It was an aggressive move to verticalize their stack. This placed pressure on other VDI vendors, who must now compete against Citrix, which owns the entire delivery chain. But it also alienated thin-client vendors who previously partnered with and advocated for Citrix and now must compete with them.

Where Citrix's move was about vertical depth, IGEL's move was about horizontal dominance. In June 2025, IGEL announced the completion of its acquisition of Stratodesk, a competitor in the Linux-based endpoint market.

Stratodesk and IGEL are both software-only companies and have long fought over the same turf and customers: converting aging PCs and thin clients into secure, managed endpoints. Stratodesk's "NoTouch" software was the primary alternative for organizations that wanted flexibility without committing to the IGEL ecosystem. By acquiring them, IGEL wasn't just buying technology; it was buying market share and removing a competitor from the table.

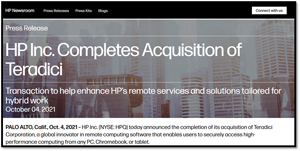

In the past year, we saw two major acquisitions in the thin-client market. A few years earlier, in

October 2021, HP acquired Teradici

, seeing this as a huge opportunity as the world was settling into hybrid work. Their main goal was to gain access to Teradici's PCoIP, enabling them to stream high-end graphics over the internet without lag. HP realized that creative pros like video editors and architects needed a way to access their powerful workstations from home, and buying Teradici was the perfect way to make that happen. Teradici was amenable to the HP buying them as VMware Horizon, one of their primary users, was developing Blast, their own protocol.

[Click on image for larger view.]

[Click on image for larger view.]

The result of this deal was "HP Anyware,"

a new software platform that combined the best of both companies and really raised the bar for the rest of the market. By bringing this tech in-house, HP enabled its power users to work remotely on graphics-intensive projects.

Final Thoughts

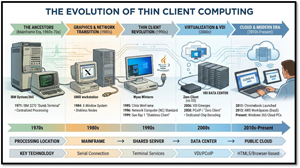

Over the last 50 years, we have seen the evolution of thin client computing. It originated in the 1970s with dumb terminals, reemerged in the 1990s with Citrix, matured in the 2000s with VDI, and has now culminated in the modern cloud era, where network-everywhere connectivity enables devices to access Desktop-as-a-Service (DaaS).

[Click on image for larger view.]

[Click on image for larger view.]

During this time, we have moved from a bazaar of small, independent OS vendors to a thin-client landscape dominated by three independent thin-client companies with very different philosophies: Citrix, with its all-in-one vertical stack; IGEL, with its bought-and-paid-for market share; and 10ZiG, with a different model than the other two.

I discussed both IGEL and Citrix earlier, but 10ZiG occupies a distinct place in the marketplace as an independent thin-client vendor.. It offers both a thin-client operating system and, if desired, the hardware to run it, as 10ZiG's thin client operating systems can function on nearly any device, including "obsolete" X86 PCs and laptops, as demonstrated in my previous article. 10ZiG has a line of zero clients for high-security use cases, something IGEL and Citrix do not offer. Many customers appreciate purchasing both hardware and software from a single provider and having a single source for support.

[Click on image for larger view.]

[Click on image for larger view.]

With the consolidation in the thin-client marketplace, the choice for IT leaders is now simpler, but the stakes are higher. You either buy into the integrated ecosystem of a VDI provider, or you can choose an agnostic endpoint operating system that connects to everything.

In this article, I focused on just the history of thin clients and the three largest independent thin-client providers. In my next article, I will provide a broader view of the VDI landscape and include other thin-client vendors.